When Ruth Fisher reported to work in September 1955 at the newly-established Iowa Lions Eye Bank at University Hospital in Iowa City, there was no official office space. Dr. Alson E. Braley handed her a shoe box with office supplies and few instructions.

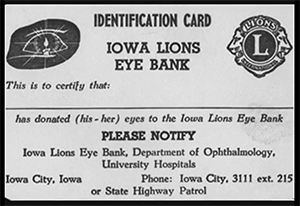

Fisher’s first order of business was to work with the Iowa Lions to design a registration card for eye donors. The first half of the card was filled out by a prospective donor, notarized, and returned to the eye bank. The bottom part remained with the donor, and they were instructed to tell their family members of their plans. Members of Lions Clubs of Iowa were enlisted to recruit their fellow residents to sign donor cards and suggest general rules and regulations for the operation of the eye bank. They also funded and placed enucleation kits in hospitals around the state.

At the time of death, a licensed Iowa physician would remove the donor’s eyes and then call Iowa Lions Eye Bank to let them know the tissue was available. The physician would place the eyes into glass vials surrounded by wet ice in an aluminum thermos-like container. The eye bank would call the Iowa State Highway Patrol, which would send a trooper to pick up the container from the physician. The container would then be delivered to the eye bank at University Hospital in Iowa City.

Fisher also developed a waiting list of those who needed cornea transplants. As eyes became available, Fisher would notify the recipient by phone that they would have to be at University Hospital within four hours.

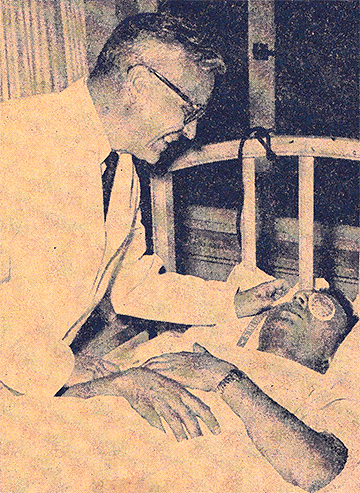

In the early days of corneal transplantation, a patient would have to remain hospitalized and lay still for up to two weeks to prevent complications and potential rejection.

In addition to overseeing the operation of the eye bank, Fisher traveled around the state educating Iowans about the eye bank and encouraging them to sign donor cards. By the late 1980s, when they were phased out, more than 100,000 donor cards had been submitted to the eye bank.